Reusable KYC: when a dedication to decentralization self-sabotages

Are we our own worst enemy?

SSI has distressing emergent outcomes — the antithesis of the hopes and plans of the SSI community and those attracted to SSI's real-world application. We have to reflect and rethink.

With thanks to those who commented on draft versions: Dil Green, Will Abramson, Ryan Worsley, Jakub Lanc, Brent Zundel, Andrei Sambra, Mihai Alisie. And to those who have influenced the ideas here in conversation and in their writing: Matthew Schutte, Jonathan Donner, Elizabeth Renieris, Kieron O'Hara, Martin Etzrodt, Michael Shea.

This document supports the launch of the generative identity working group[1], and emerges the week of the 31st Internet Identity Workshop[2] and in good time for the Odyssey Momentum hackathon.[3]

Put starkly, many millions of people have been excluded, persecuted, and murdered with the assistance of prior identity architectures, and no other facet of information technology smashes into the human condition in quite the same way as ‘digital identity’. Therefore, if ever there’s a technological innovation for which ‘move fast and break things’ is not the best maxim, this is it. We need to move together with diligent respect for human dignity and living systems.

The SSI community is writing a book for publication in 2021 (referred to from here on simply as ‘the book’):

This case study-driven book cuts through the jargon and hype to expose the amazing potential SSI offers for security, privacy, identity, and even uprooting the way the global economy works.

The chapters and appendices are all listed on the publisher’s website at the time of writing[4].

Based on previous analysis, the editors invited me to contribute a chapter with the title “SSI: our dystopian nightmare”. While it is a challenge to address its flaws in one chapter, it was nevertheless a privilege to be invited to do so and a testament to those extending the invitation. This document evolved from a draft of that chapter, and the chapter will now evolve from this document.

The book blurb says "you’ll reach the book’s lightbulb moment: what this radical technology really means for the shape of our lives, our businesses, and our futures." Unfortunately, the story to date has been largely utopian, an impossible future.

No-one works on SSI to deliver outcomes diametrically opposed to the ones they set out to procure. But that is what’s happening.

I urge you to read on because — regardless of your job, your skills, your experience or your professional goals — you have an ethical responsibility to yourself, your colleagues, your friends and your family if you have any influence in this context at all.

I invite you to press pause on any SSI project you may be involved in while you consider the potential dystopian consequences of your work, and if you don’t have authority over the pause button, do make sure that those that do read this document.

If you or they don’t fully understand the deep concerns outlined in this document — my apologies. I entreat you to work with a tech-savvy social scientist in one day of joint reflection. Just one day.

Why a social scientist?

Although SSI has been scoped, architected and built as technology, it is not merely technology. By definition, it’s sociotechnology (involving the application of insights from the social sciences to design policies and programs[5]). Yet when I’ve asked if any disciplines other than technology and law have actually been invited to the party thus far, the question has always drawn a blank. No reference to psychologists, sociologists, ecologists, historians, political scientists, etc.

This is alarming simply because people don’t work like software works. The SSI community’s mission breaks on contact with people if there is even a chance that people will ‘break’ on contact with SSI.

One has to go no further than the title of the book’s first chapter to bring a mono-disciplinary myopia into focus:

Chapter 1: Why the Internet is missing an identity layer — and why SSI can finally provide one.

SSI cannot provide an 'identity layer' of the Internet any more than the Internet might be said to be missing a ‘truth layer’. Such deep and meaningful concepts manifest amongst human beings. They can’t be slotted into the technology stack alongside the likes of TCP/IP, UDP, and HTTP[6].

When the SSI community refers to an ‘identity layer’, its subject is actually a set of algorithms and services designed to ensure the frictionless transmission of incorruptible messages between multiple parties. This involves some clever mathematics and neat code that will undoubtedly prove of some value in the world with appropriate tight constraints, and it will certainly impact the operation of various conceptualisations of identity, but this is not human identity per se, or the digitalization of human identity. Far from it, as we shall see.

First, we take a brief journey into emergent consequences. Then I’ll introduce two broad categorisations of conceptualisations of human identity developed specifically to help make sense of the possibilities and ramifications of identity technologies. We conclude with a brief look at the implications of the first two sections in terms of our collective intelligence and ability to address wicked problems together.

I know from experience that this isn’t an easy subject to talk about — ‘digital identity’ is such a broad, deep and multi-faceted field. If you are an expert in sociology or philosophy, psychology or cultural studies, complexity, history, economics or law or some other relevant discipline other than information technology, I urge you to expand on this analysis to help throw more light on the matter.

With brevity in mind, let’s select just one key sentence from the book’s first chapter:

this means the best overall analogy for the decentralized identity model is in fact exactly the way we prove our identity to each other every day: by getting out our wallet and showing the credentials we have obtained from other trusted parties.

Unfortunately, this assertion is dangerously misleading.

We’re a quarter of a century into the development of social media (in the context of the World Wide Web), and so with the benefit of a hindsight we don’t yet have for SSI, how does this read to you? ...

this means the best overall analogy for social media is in fact exactly the way we converse and interact every day: by sharing things to talk about and expressing our thoughts as we do with current media — phoning, writing, emailing.

There are some critical qualities missing here. Not because it isn’t precisely equivalent to Chapter 1’s claim for SSI but rather because we all know better after the fact. This assertion for social media lacks any acknowledgement of complex adaptive systems, of media theory, or of our understanding of human behaviour. It fails to anticipate the emergence of outcomes wholly different from prior experience.

I’m not saying that social media does not have some wonderful qualities but that it has also contributed to the decline of traditional media and to the development of filter bubbles, viral fake news, state surveillance, surveillance capitalism, political polarisation and extremism, revenge porn, cyberbullying, Snapchat dysmorphia[7], pro-suicide fora, smartphone addiction, etc. The least we can do now then is to invest time with social scientists and other disciplines to ask what unintended consequences will accompany large-scale adoption of SSI. There is no evidence that this has happened to date.

I can write “will accompany” rather than “may” because complex adaptive systems behave differently when core system properties are radically altered (and sometimes even when slightly altered). For example, friction is a core property of systems of identity just as it is for the media through which we communicate. Digitalization removes the frictions associated with the time and energy required to manage atoms, traverse space, and search and access archives. And just to note that, like any system property, friction cannot be said to be a good or bad thing out of context, and I will explore this in the current context later.

In seeking to better understand the unfamiliar by reflecting on the more familiar, we can think about behaviours we exhibit or have seen others exhibit in the context of social media and the potential or indeed likely equivalent behaviours and consequences in the context of SSI.

We change ourselves, consciously and subconsciously, when we know we're the subject of gaze. It’s a perfectly natural response. The gaze doesn’t have to be active to ‘make’ people behave in ways they wouldn’t otherwise. For example, have you seen people ‘Instagram™ming’ themselves into a scene and wondered whether they actually appreciated the occasion or even took in the scenery? Are they present? They were perhaps emotionless up until the smartphone made their arm raise to head height (or in fact just above for ‘just the right angle’[8]), and then came postures and smiles to meet the gaze. Pity the selfie-generation!

Another noteworthy behaviour is the readiness of social media users to transgress their own privacy norms in the moment — the so-called privacy paradox[9]. Or perhaps we don’t personally appreciate or care about any potential consequences of a privacy breach in a given context. Quite naturally, we behave with immediate self-interest rather than the system’s longer-term best interests in mind.

In the same vein as these examples … What verifiable claims do you need in your wallet? What’s the ‘must-have’ this week? You don’t want to stand out by failing to follow suit. Hey, have you seen this new feature that lets you self-verify your total number of verifiable claims? And this social network just made it easy to publish claims openly[10]. Everyone’s doing it.

What if the only thing standing between you and making a living is a verifiable claim that you’ve had covid-19, presuming some corresponding immunity. Miserably, a fraction of society has to ask themselves if they should go get the virus for just this reason, and a fraction of those then do.

Perhaps you’re thinking that behaviours resulting from the adoption of SSI are not the SSI community’s responsibility? But they are — just refer to the ethical framework of your professional engineering body. Or perhaps you’re hoping people just won’t behave in ways that can be seen, upon some reflection, to produce negative outcomes at system scale. But the behaviours make individual sense in the contextual moment. We operate with self-interest in mind, rarely system-interest. It’s simply how we are — even those who might be said to have given it some thought, as epitomized by a story tweeted by Daniel Buchner[11].

Daniel leads technical product work for Microsoft’s decentralized identity initiative and recently engaged a medical doctor in conversation on the topic. He was appalled to hear the doctor conclude that social security numbers should be applied everywhere, and that they should be publicly known to represent us.

You may have some long-lasting relationships on Twitter or Wordpress or Medium or WhatsApp or Facebook or Reddit or wherever, just as you do in the ‘real world’. Each takes its own course with some things revealed, others things kept private, other things merely left unreferenced. And some of us have even been known to exaggerate a few things on occasion. We try out different personae on different platforms, in different locations, in different contexts. This is all quite natural, part and parcel of being human.

Our identities, our selves, are formed through internal narratives. The internal narrative is informed by the interactions. And the interactions are modulated by the identities. Social, reciprocal, concurrent, and forever in flux.

An acquaintance now quits those ‘old-fashioned’ relationship-building niceties and gets straight to the SSI point. Where do you work? Which college did you go to? Which college did your parents go to[12]? Republican or Democrat? What’s your gender? Your ethnic origins? Do you have this gene or the other one?

If you fail to offer up the requisite verifiable claims then you fail to get to ‘trust building’ first base in the SSI century. (Note: this is in fact trust avoidance not trust building[13].) You are then ignored or indeed rejected. But it’s worse. The new social norm now expects you, expects everyone, and more accurately expects your agents to perform similar examinations as a matter of course. And why not? We’re told it’s beneficial, that it’s trust building, that it's the missing layer. It’s frictionless. It works on an individual basis and government services have adopted it, so surely then it must be good for society as a whole?

There is no known way to constrain SSI from enabling if not catalyzing these applications. Such constraints might require a friction or a frustration of interoperability entirely counter to the architectural and engineering goals.

Professor Lawrence Lessig is a scholar of technology in society who is famed, amongst other things, for exploring the ways in which our lives are subject to four forces: laws, social norms, the market, and technical architecture (software)[14]. He observes that software code regulates conduct in a similar but not identical manner to legal code — while law needs people to know about it to be effective in regulating behaviour, software code is effective regardless.

SSI fundamentally changes the balance of these regulators in the context of identity. It diminishes the role of legal code and has software code and social norms supervene. (When it comes to identity, let’s all hope legal code keeps the market well clear — a market in digital identity leads to digital enslavement.)

In centralising identity on the individual, as SSI does, it removes some identification, authentication, and claims processes from being subject to law and organisational governance (e.g. the GDPR[15] does not apply to individuals), and into the chaos of social groups and the formation and reformation of social norms and other societal structures. It’s worth noting that social norms form without any real and widespread understanding of the technology and with little if any appreciation for potential emergent consequences. Unfortunately, as we know very well from history, emergent social norms can be very far from egalitarian or liberating (e.g. Nazism, apartheid), and although the decentralized authentication processes we have today have their downsides of course, those disadvantages are at least well understood and remain the constant subject of expert legal purview.

Now I must point out that I’ve taken some licence in switching around the more typical attribution of decentralization to SSI and centralization to today’s status quo. On one level this switch is accurate — our relationships with dozens of organizations today are indeed authenticated by each of them in turn, separately[16], whereas SSI collapses that all down to our supposed atomistic selves. However, we must be cognizant that each and every layer of any ‘stack’ may be measured separately for its degree of (de)centralization and found to be quite different. There is no aggregate quantification, only varied systemic outcomes.

Even more pertinently then, we must appreciate that invoking “decentralization” as if it were an end rather than a means is pointless. Rather, as Nathan Schneider argues convincingly[17], we need to be really specific about our purpose and therefore also our facilities for course-correction. While further discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of this document, it’s worth lifting a short quote from Nathan’s conclusion:

... we cannot accept technology as a substitute for taking social, cultural, and political considerations seriously. Decentralized technology does not guarantee decentralized outcomes.

I understand that the SSI community has proceeded to date with deliberate separation of the technical from the political[18]. However, in the context of identity particularly, these are in fact inseparable and to pretend otherwise is unethical.

Now that I have begun to outline the nature of potential consequences, indeed very likely consequences by my estimate, it’s time to explore a possible categorisation of all things ‘identity’ that will help throw some more light on the flaws of SSI, and to help us all develop a better way forward.

The word ‘identity’ encompasses many different things in many different contexts, and it can even take opposing forms. For example, the SSI context is very much one of individualistic distinction, but there is also of course collective or cultural identity based on similarity (the word identity is derived from the Latin ‘idem’ meaning ‘same’). If you find the complexity here intriguing, I recommend starting with “Identity: A Very Short Introduction”[19], but otherwise rest assured that this section is accessible.

Let’s play a game[20]. In fact, we already are. In business we may ask ‘what game are you in?’, and everyday language may refer to life itself as a game.

We — the physical, biological human — do not enter games directly. Rather, we select or define an avatar. This might take the form of a Tyrannosaurus rex in more recent editions of Monopoly™. Similarly, computer games, most notably massively multiplayer online games, carry this idea quite naturally into the digital age. The likes of Monopoly and Final Fantasy are artificial inventions of course, but then so is the law, and our avatar in that game is known as a legal identity.

We can say that sociologists and psychologists regard our everyday identities in a similar fashion. Intuitively following some self-reflection, we all know that we have different identities, call them personae if you like, or avatars, that we adopt in different contexts. Indeed the word ‘person’ has its roots in the Latin ‘persona’, meaning an actor's mask, a character in a play.

All the world’s a stage.

I referred to this earlier in the context of ‘being’ different across different social media in different contexts, and constantly revising those identities based on the corresponding contextual relationships and interactions. Consider your professional avatar, your parental avatar, your spousal avatar, your student avatar, etc. Overlapping and interacting in some respects no doubt, but always evolving and always contextual[21]. (SSI cannot communicate context.) Your ‘you’ in the performance review meeting at work differs to your ‘you’ on your wedding day. Your avatars at age 35 will differ from those age 25, or indeed from those age 34. Or 34½. Or yesterday. Psychologists and sociologists understand all this well.

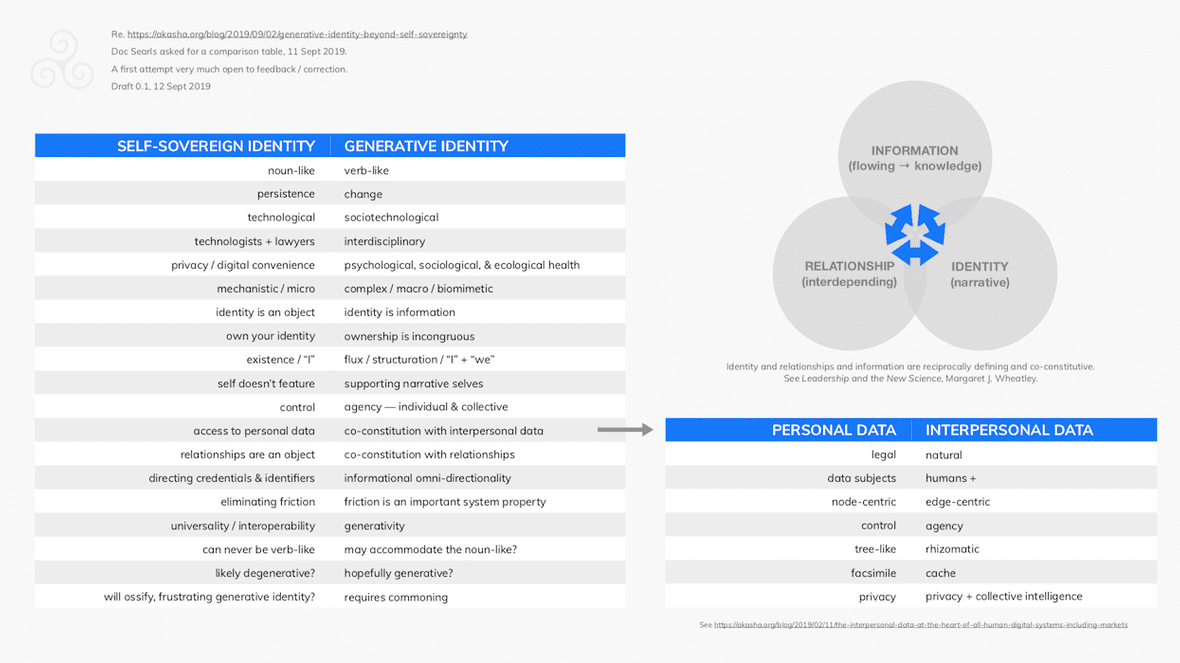

The AKASHA Foundation[22] funds research to bring clarity to the topic of ‘digital identity’ to help ensure that corresponding innovations benefit the individual, our communities, our species, and by corollary those species with which we share this planet. With the aspiration of avoiding so-called rabbit holes in the domain of identity, we have found it useful to categorise different conceptualisations of identity as either noun-like or verb-like.

Verbs describe actions, states, change — in fact then the very nature of living things and living systems.

As Buckminster Fuller anticipated in ‘I Seem to be a Verb’[23] ... who I am encompasses a constant flux of informational diffusion and intermixing, interfacial constructions and experiences, continuously revised narratives, arrangings and organizings.[24]

Your “I”, and your “you” from others’ points of view, are always changing, often gradually, occasionally radically. It’s how we keep re-orienting our understanding of others and re-orienting ourselves in social contexts.

On the other hand, birth certificates, social security numbers, driving licenses, and passports are noun-like — they're not intended to be dynamic, by design. They are artificial, as Phil Windley notes so well[25]:

Descartes didn't say "I have a birth certificate, therefore, I am."

The game of law — a relatively recent bureaucratization — requires noun-like identities. The game of life involves verb-like identities.

The art here then is ensuring that the essential human qualities encompassed by verb-like identities are accommodated by systems of ‘digital identity’, or not obliterated by them at the very least.

In light of the earlier discussion here, it would be foolhardy to rely on individual human behaviours to secure the continuing system viability of verb-like identities in a SSI world. Can software code help here then? In the same post as the Descartes observation, Phil Windley writes:

We are at a point in the development of identity that it is possible to develop and deploy technologies that allow individuals to create a self-sovereign basis for their identity independent from civil registration.

Such systems allow us to tease apart the purposes of the birth certificate by recognizing a self-sovereign identity independent of the proof of citizenship. This doesn't, by itself, solve the problem of providing legal identity since the self-sovereign identity is self-asserted. But it does provide a foundation upon which a legal identity could be built: specifically it is an identifier that a person can prove they control. Constructing a legal identity on this self-sovereign identity is possible, but would require changes to existing statutes, rules, policy, and processes.

To translate this into the lexicon here, SSI cannot substitute for the need for legal (noun-like) identity, nor is anyone asking that of it, but it can evolve to become its own form of noun-like identity with the potential to help support the formation of an alternative legal or quasi-legal identity. This is useful in terms of the target included under the Sustainable Development Goals to ensure everyone has a legal identity by 2030[26] (those living without legal identity are powerless in the game of law), yet there is no reference to or acknowledgement of what is presented here as verb-like identity, nor anywhere else that I’ve found.

The book presents seven scenarios in Chapter 3 to explain varying applications of SSI. While I don’t have permission to reproduce the explanatory diagrams here, I can list the scenarios:

The accompanying diagrams portray so-called ‘trust triangles’[27], with each triangle encompassing a credential issuer, a credential holder, and a credential verifier.

Scenarios 4 and 5 involve a Government ID agency as issuer, i.e. issuers of legal identity. Scenarios 6 and 7 do not, but they do involve banks that require the Government ID agency in the opening of new bank accounts per scenario 5.

Legal (noun-like) identity features obviously then in the majority of the scenarios presented. This is no accident because this is how the SSI community thinks, and how it thinks is reflected in the technical architecture and documentation. For more evidence, a diagram in Chapter 2 titled “An overview diagram of the role of agents and wallets in the SSI ecosystem” only references people in their capacity as legal actors.

SSI does not recognise the verb-like let alone step up to the challenge of sustaining or empowering verb-like identity in the digital age. Any solace a reader may seek in scenarios 1, 2 and 3 is unfounded, as I’ll now explain.

SSI proxies for legal (noun-like) identity, but the system property of friction is radically altered in the process. Historically, invoking legal identity is tiresome. It involves systemic friction and consequently it’s called upon only when really needed and ignored in all other contexts. How frequently and for what purposes have you needed to produce proof of legal identity so far this century?

But SSI demonstrates an unprecedented frictionless quality enabling the routine, programmatic proffering of or triangulating back to legal identity and other noun-like identities[28] and associated credentials on demand.

We can consider this in terms of how playing the legal game impacts other games following the introduction of the SSI game.

An individual’s legal (noun-like) identity is a 1st-order avatar in the legal game. A 1st-order avatar in the ‘real’ world, in the game of life, is verb-like. Neither is reliant on the other but relates directly back to the player, i.e. the physical human being. A marriage (a legal contract) and a corporate (a legal construct) are 2nd-order avatars in the legal game as 1st-order avatars are prerequisite. A subsidiary company would be 3rd-order, etc. Similar orders, or more accurately holons, play out in all games.

There are comparatively new games in town based on cryptography. SSI is one such game. Ethereum[29] and Holochain[30] are other examples. Decentralized identifiers (DIDs) are 1st-order avatars in the SSI game.

When a connection is made between one’s SSI avatars and one’s legal avatar, and assuming the legal game continues to trump cryptographic games in human society, the SSI avatar becomes subordinated to the legal avatar wherever and whenever the corresponding verified claim is or has been present. As you’ve seen, this doesn’t just apply in a ‘trust triangle’ with a Government ID agency, but in adjacent ones too such as a triangle involving a bank that’s party with you to another triangle with a Government ID agency. And so to adjacent adjacent ones, and adjacent adjacent adjacent ones, etc.

Triangles are to be found everywhere there is a need for structural rigidity — e.g. the Manhattan Bridge, the Eiffel Tower, bicycle frames — and similarly ‘trust triangles’ achieve informational rigidity with informational triangles. This is the kind of outcome those in the West decry of China’s nascent identity and social credit system[31]. One might congratulate them at least for recognising and being clear about what they’re building.

Please note that I’m not saying SSI leaks claims information. This isn’t about information security or the prevention of identifier correlation. This is about Alice’s freedom, perhaps indeed her “sovereign right” if that’s how you conceive the world, to live and live through her verb-like identities most of the time as she does today. It’s noteworthy that SSI doesn’t have a monopoly here — digital identity initiatives in other cryptographic games such as Ethereum have similar causes-and-effects.

The SSI community is dedicated to digitalizing noun-like identity, and because there’s no equivalent effort to achieve the same for verb-like identity, let alone one that might have the sociotechnological capacity to resist the otherwise inevitable creep of digitalised noun-like identity, SSI inexorably suffocates the verb-like.

It seems I must be a noun ...

... except that is of course oxymoronic. There is no such thing as a noun-like “I” compatible with the game of life. That would, for example, make you exactly the same as the five-year old starting school, and the young adult on his/her first day at work, in every context, in every game. Indeed, a noun-like “self-sovereignty” is impossible — to play the SSI game is to be trapped in it. The SSI system is sovereign and you are left anything but.

Perhaps by inheriting a noun-like conceptualisation of identity from legal code, perhaps in consequence to the assembly of SSI from cryptographic primitives, and perhaps in response to a perceived inclination of SSI community members to reify the individuated, atomistic person, the SSI worldview may be described as Newtonian in contrast to the complexities of living systems.

This worldview doesn't just mistake legal identity for 'the real thing'. The legal construct of personal data[32] is similarly mistaken, leaving the actual real thing open to unthinking entanglement with the legal construct of property. But the world doesn’t work like this.

The major problems in the world are the result of the difference between how nature works and the way people think.[33]

After Margaret Wheatley[34] (see the figure below), identity is the sense-making capacity of organizing. It is of the selves that organize and the self that gets organized. Narrative in nature, identities assemble in relationships involving and producing personally and socially material information.

Relationships are the pathways for organizing, required for the creation and transformation of information, the expansion of the organizational identity, and accumulation of wisdom. Relationships are formed with information exchange between identifying / identifiable entities in identifying / identifiable organizings.

Information is the medium of the organizing. Life uses information to organize itself, i.e. when a system assigns meaning to data. Information is contextual to identities in relationships.

There is no such thing as personal data in the game of life but rather interpersonal data — created in and associated with identities in relationships. Almost every type of data you can think of that meets the legal definition of personal data turns out to be interpersonal in reality (the other ‘person’ may be an organization of people). Keeping a personal diary may exemplify a relatively tiny set of exceptions, although even then one can think of it as one of your verb-like identities seeking to understand and help another. Selves-reflection.

Identity and relationships and information (interpersonal data) are reciprocally defining and co-constitutive. In the jargon of graph theory[35], interpersonal data is edge-centric not node-centric, and indeed so then identity and relationships. (I noted in the caption to the figure above that three circles may not be the best representation.)

It is critical to understand this if only because we have come to a point in history when humanity has to rise up to wicked problems at global scale for the very first time. Fortunately, we’ve inherited some almost magical information technologies that should help us learn, understand, and cooperate, but there are still many ways in which we can misjudge their application.

As you will appreciate, interpersonal data needs to be privacy preserving and socially meaningful. It might be your road trip but those with responsibility for transport infrastructure will want to monitor road use. It might be your immunisation, but those responsible for public health will want to ascertain herd immunity. It might be your life, your family, but we will need to join-up somehow to help you and your family live your lives in privacy, in peace, in harmony, and in prosperity, in the face of such challenges as the climate cataclysm and pandemics. The system-interest is in your self-interest just as your self-interest is in the system-interest.

Contrast this with the book’s description of the advantages of SSI in the context of personal data (Chapter 8):

As those accounts convert over to using pairwise peer DIDs and signed personal data, the value of that personal data to anyone else but the relying party who has explicit signed permission disappears.

When you nail down identity you’re in the mindset to nail down interpersonal data. Its social value disappears as we’re informed here, or at the very least frustrated. Such frustration leads many to scrabble for the legal concept of property[36] to try and get it moving again, but the full, natural opportunity and value comes in not nailing it down and propertizing it in the first place.

This characteristic of SSI is presented as a feature when it is in fact a bug of existential importance. It’s degenerative — i.e. characterized by progressive deterioration and loss of function.

The same applies to any technical architecture that designs to treat personal data and identity as separate concerns. If the architecture pays heed only to noun-like identity, and/or if it conceives of personal data as some separate thing that can be shepherded into a personal data store / bank / vault, then it’s working against our best interests however worthy the corresponding team’s motivations.

Such designs fail the law of requisite variety in our living systems to the significant detriment of our psychological, sociological, and ecological well being. As articulated by the Six Circle Model[37], designs to effect any system change — let alone ambitions for global systemic transformation — too frequently focus on structure, process, and patterns, and neglect the underlying inseparable fundamentals of identity, relationships, and information (interpersonal data). Such neglect leads to failure.

The question of ‘digital identity’ is massively more critical than many working on it appreciate.

Needless to say, this document does not substitute for the much-needed interdisciplinary research into SSI in the context of the theories and reality of technological and social change, but it is I hope evident that the claims throughout the book for SSI’s social advantages — e.g. privacy, trustworthiness, decentralization, agency enhancement, and even “sovereignty” — cannot be made for SSI technology. They are entirely unverified claims.

Social claims only make sense in the context of SSI technology in people’s hands, in society at large, as sociotechnology, and we must all be explicit today in letting everyone know that this combination, this assemblage, has received negligible analysis let alone synthesis to date. Such deliberations are essential in advance of allowing any SSI game to begin.

Until perhaps further research proves otherwise, I err on the side of caution. SSI cannot deliver the system properties we need for ‘digital identity’. If it cannot be tightly constrained in some as yet unknown way to very occasional instances of noun-like identity, then it will deliver outcomes diametrically opposed to the ones the SSI community set out to procure. Viewed atomistically, technologically, SSI looks quite sensible. At scale, as sociotechnology, the emergent consequences are malignant.

A community is forming under the banner of generative identity[1:1]. By generative I mean ‘participating as nature’. It denotes a capacity to produce unprompted change, growing not shrinking the possible; a capacity for leverage across a range of tasks, adaptability to a range of different tasks, ease of mastery, and accessibility[38]. At the time of writing, generative identity is a label for a set of challenges to SSI and some heuristic principles presented as discussion points in the hope of both avoiding very poor emergent outcomes and creating the conditions to support psychological, sociological, and ecological health.

Generative identity is about the human’s potential and humanity’s potential. I hope you will identify with that.

Bunge, Mario. 1999. Social Science Under Debate: A Philosophical Perspective. University of Toronto Press. ↩︎

Is "Snapchat Dysmorphia" a real issue?. Ramphul and Mejias, Cureus, 10(3), 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5933578/ ↩︎

See https://www.allure.com/story/how-to-take-good-selfies if you’re an Instagram newb. ↩︎

A privacy paradox: Social networking in the United States. Susan Barnes, 2006, First Monday, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5e30/227914559ce088a750885761adbb7d2edbbf.pdf ↩︎

The GDPR does not proscribe individuals from publishing personal data or organizations from helping them do so. Moreover, the social network itself may be decentralized (not entailing an incorporated entity) and not then subject to such regulation. ↩︎

https://twitter.com/csuwildcat/status/1236071204768731137 ↩︎

A first “trust triangle” has Bob as the holder of the claim and his parents as issuers, and their credibility as an issuer is confirmed by a second triangle in which they are the holder of a claim and their respective college the issuer. They appreciate this claim may be socially useful to Bob so have the verification process ‘on auto’. ↩︎

See https://www.ted.com/talks/onora_o_neill_what_we_don_t_understand_about_trust ↩︎

Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace, Lawrence Lessig, 1999, see http://codev2.cc/about/ ↩︎

General Data Protection Regulation, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Data_Protection_Regulation ↩︎

Excepting where individuals may select a “log in with …” option, bringing a third party such as Facebook or Google into the process. ↩︎

Decentralization: An Incomplete Ambition, Nathan Schneider, 2019, https://osf.io/m7wyj/ ↩︎

Private correspondence with an SSI thought leader. ↩︎

Identity: A Very Short Introduction, Florian Coulmas, 2019, https://global.oup.com/academic/product/identity-a-very-short-introduction-9780198828549 ↩︎

Inspired by — Me and My Avatar: acquiring actorial identity, Anthony O’Tierney et al, 2016, https://researchrepository.ucd.ie/bitstream/10197/9328/1/F54_Avatars_EGOS_2016.pdf ↩︎

I Seem to be a Verb, Buckminster Fuller et al, 1970, https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/I_Seem_to_Be_a_Verb.html?id=wBUJrgEACAAJ&source=kp_cover&redir_esc=y ↩︎

Generative identity — beyond self-sovereignty, Philip Sheldrake, 2019, https://akasha.org/blog/2019/09/02/generative-identity-beyond-self-sovereignty ↩︎

Self-Sovereign Identity and Legal Identity, Phil Windley, 2016, https://www.windley.com/archives/2016/04/self-sovereign_identity_and_legal_identity.shtml ↩︎

Target 16.9, Sustainable Development Goals, 2015, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg16 ↩︎

See https://www.windley.com/archives/2018/09/multi-source_and_self-sovereign_identity.shtml ↩︎

Many organizations and bureaucracies have a noun-like approach e.g. your employer assigns an employee number that endures. ↩︎

Article 4, General Data Protection Regulation, 2016 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679&from=EN#d1e1489-1-1 ↩︎

An Ecology Of Mind — A Daughter's portrait of Gregory Bateson Directed by Nora Bateson, 2015, https://vimeo.com/ondemand/bateson/116642860 ↩︎

A simpler way, Wheatley and Kellner-Rogers, 1998, https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/634222616 ↩︎

See https://medium.com/radicalxchange/the-interpersonal-data-at-the-heart-of-all-human-digital-systems-including-markets-6316701184a9 ↩︎

The Generative Internet, Jonathan Zittrain, 2005, https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/9385626/Zittrain_Generative%2520Internet.pdf?sequence=1 ↩︎